NTSB releases 2019 Lincoln County gas pipeline explosion summary report

Published 4:46 pm Thursday, March 18, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

• Click here to download explosion scene photos

The National Transportation Safety Board has released thousands of pages of information from its investigation into the Aug. 1, 2019, natural gas pipeline explosion in Lincoln County.

The pipeline, owned by Enbridge Inc., and operated by Texas Eastern Gas Pipeline Co., ruptured at 1:20 a.m. at the Indian Camp area off of U.S. 127 in northern Lincoln County which killed Lisa Derringer, and injured five others. The affected area spanned about five acres; five homes were completely destroyed, while 14 others were left virtually untouched.

People from as far away as Lexington reported seeing the inferno in the sky.

Officials said a resident who was leaving the scene of the incident described it as looking like Mars — the affected area has no trees or grass left, and an asphalt road in the area was turned into gravel.

The NTSB project summary report released to the public last week contains about 3,200 pages of technical surveys, inspections, reports, graphs, interviews, history, and photos involving the pipeline, its explosive rupture, and massive fire.

According to the report the accident happened in an open field on property owned by Texas Eastern, which Enbridge refers to as Line 15. It was 30 inches in diameter and buried about 43 inches deep.

The closest valve stations with block valves that could manually control the flow of gas through the segment of the pipeline where the accident occurred were located about 4 miles northeast and 14.9 miles southwest of the explosion site. Neither valve station was capable of remote operation, according to the document.

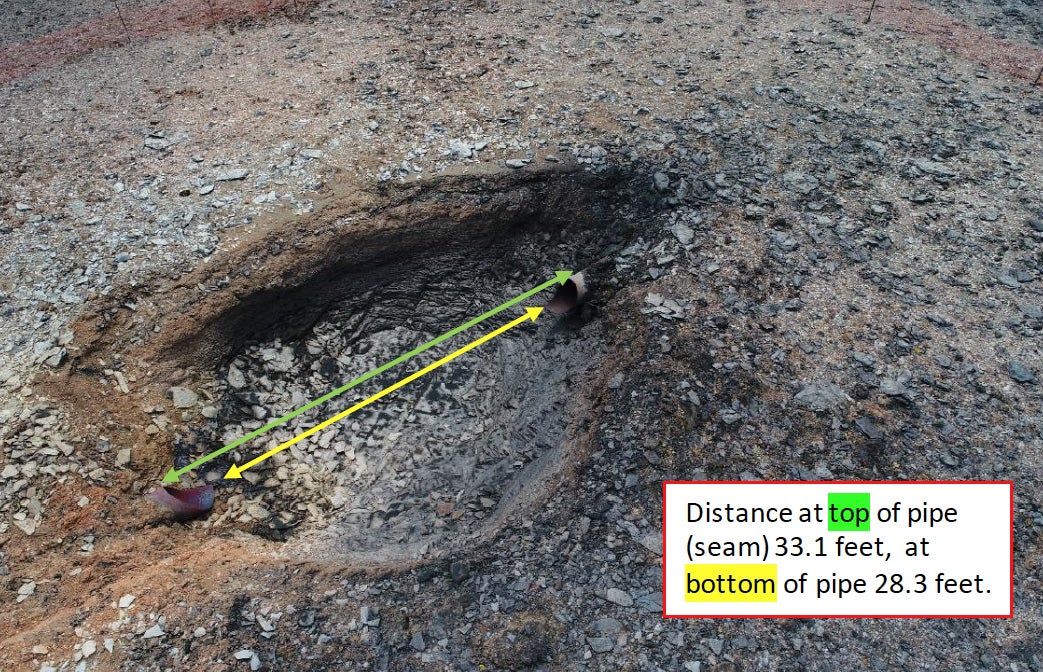

The crater that resulted from the explosion was 55 feet long, 35 feet wide and about 12 feet deep. “Two short segments of pipe, that had been attached to each end of the ejected segment of pipe, were visible at both ends of the crater pit, protruding from the crater walls.

“The segment of ejected pipe, measuring about 33 feet in length, which was discharged from the crater in the explosion, became airborne and traveled in a southerly direction. The segment of ejected pipe, which was estimated [by the investigation119] to weigh about 3,900 pounds, came to rest on open ground, about 481 feet to the approximate south of the crater location.”

According to the report, “Prior to the rupture, no excavation work had been witnessed in proximity to the rupture site. Enbridge employees had most recently been in the immediate area on July 18, 2019, to check on the casings near the Norfolk Southern railroad tracks.”

The report states that a Lincoln County Deputy Sheriff was rescuing two people fleeing from the disaster in his cruiser when he saw a body lying on the ground. He stopped to help, but saw that the person was dead, and the intense heat prevented him from going further and he received thermal burns on his hand.

Other deputies tried to retrieve the body, who was later identified as 58-year-old Lisa Derringer, but was unable to, also because of the heat from the flames that were 640 feet away. About 15 minutes later the deputies borrowed firefighter equipment and retrieved the descendant.

Later, the state medical examiner determined Derringer died of “pulmonary barotrauma, and second- and third-degree burns on 50% of her body.

Two surveillance cameras located about 1.5 miles and 3 miles away showed investigators that at the time of the explosion, “displayed two distinct sequential flashes of extremely bright light and subsequent continuous illumination of the flare of the burning natural gas that was released from the breached pipeline. The time interval between the two distinct sequential flashes, as displayed in the recorded video camera imagery, was observed to be about 10 seconds in duration”

The report states that Enbridge proved it had developed and performed “outreach activities” where it annually distributed printed materials to residents near its pipelines that promote the “811 call before you dig” program, and other documents with pipeline safety information.

The NTSB report also describes several agencies’, as well as Enbridge’s “After-Action Reviews.”

This is a view of the point cloud with measurements of the missing section of pipe.

Other information in the report includes in part:

• On Sept. 8, 1958, when this section of the pipeline was installed, during the first field hydrotest just about 100 feet southwest of the 2019 rupture location, a break occurred. It was determined that the failure was due to slag inclusion (when a piece(s) of nonmetallic substance is trapped within a weld. It is a welding error, and when it occurs at the long seam, is considered a manufacturing defect) in the pipe’s longitudinal seam weld. “The failed section was cut out and replaced with 20 feet 5 inches of the same vintage pipe.”

On Sept. 9, 1958, the line was retested and a leak occurred a few feet away. “… this leak was cut out and replaced with 6 feet of the same vintage pipe.”

• On May 8, 2019, Danville CS experienced an unplanned emergency shutdown (ESD). An ESD is designed to protect a compressor station and its personnel from threats. During an ESD, automated block valves isolate the station from the main pipeline system and automated blow-off valves release the isolated gas to bring the pressure in the station down to atmospheric pressure. Investigators found that it was caused by a shorted wire in a direct-current circuit. “Which, after a series of events, caused a buildup of pressure at the station which triggered the ESD. When the ESD initiated, one of the block valves at the station failed to close properly, allowing gas to continue to flow. Due to the continued flow of gas, the gas control center (GCC) believed there may have been a rupture near or within Danville CS.

During this incident, the station operator on-duty was the same person on-duty during the August 1, 2019 rupture. In response to a call from the GCC, the station operator manually closed a valve at the station. This did not halt the flow of gas, as the system was experiencing a valve-operation failure, not a rupture. Neither “the Station Operator nor the Gas Controller viewed the station graphics during the event.”

• On Aug. 1, 2019, at 1:24 a.m., one minute after the pipeline explosion, the gas controller in Danville received a “rate-of-change” alarm on Line 15. “Total time from initial indication of rupture to isolation was 55 minutes. The technician that closed the isolation valve was operator-qualified with unexpired certificates of completion.”

• On the date of the explosion, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration” (PHMSA) gas transmission integrity rule only applied to pipelines located in more populated areas. “As such, Enbridge was not required to implement any of the regulations … for the area containing the rupture site, including risk assessments or integrity assessments. However, Enbridge did perform voluntary risk assessments and integrity assessments in non-HCA (non-high consequence areas), including in the area containing the rupture site.

• On July 1, 2020, PHMSA added moderate consequence area (MCA) to the definitions contained within the Code of Federal Regulations. “An MCA is defined as an onshore area within the potential impact radius that contains either five or more buildings intended for human occupancy or specific types of roadways. Had this regulation been in place at the time of the accident, the rupture area would have been deemed an MCA, because the potential impact radius contained seven buildings intended for human occupancy.

• “In early 2019, Enbridge leadership determined that their current approach to integrity management was ‘not yielding the performance level consistent with [their] expectations and risk tolerance’ due to several pipeline failures on Enbridge pipelines in 2018 and 2019. Enbridge re-defined integrity management program success as “not [having] any more ruptures — with confidence, driven by facts and data.’ Enbridge states they changed their mindset to reflect that all assets were considered subject to potential integrity threats, and if reduction of ‘risk could not be proven by facts and data, the risk was assumed to be present and actions were taken to mitigate or prove’ there was no risk. Enbridge began an ‘iterative transformation of [their] organization, programs, behaviors, data, and support systems with the goal to ‘prove the integrity of [their] assets using a quantitative, as opposed to a qualitative, approach to risk assessments.’ Enbridge estimated this process would take 3 to 5 years to complete, placing completion around the end of 2023.

• Post-accident, Enbridge stated they intend to achieve their “goal of zero ruptures with confidence” through several long-term plans.

Danville attorney Ephraim Helton is representing 85 clients in a lawsuit that was originally filed in July 2020 in Lincoln County Circuit Court against Texas Eastern Transmission LP; Spectra Energy Operating Co. LLC; Spectra Energy Transmission Resources LLC; Spectra Energy Transmission Services LLC; Spectra Energy Corp.; Enbridge U.S. Inc.; NDT Systems & Services (America) Inc.; NDT Global LLC; and “an unknown Danville compressor station operator.”

Helton said several other local attorneys are also representing other clients who were affected by the blast. In September, his case was removed to federal court. However, they have asked the federal judge to remand the case to Kentucky State Circuit Court, and they’re waiting on the answer.

Once NTSB releases its final report, hopefully within six to eight weeks, Helton said they will be able to proceed with the discovery phase of the case.

No court date has been set in Helton’s case, but they do have a 5-day mediation scheduled in May.

Read the complete NTSB report at https://data.ntsb.gov/Docket?ProjectID=99981