Stanford mourns loss of Main Street barber

By Joshua Qualls

STANFORD — When Pat Sanders felt so unwell that he had to close his barbershop in February for the first time in 58 years, he didn’t realize it would also be the last.

Despite finding out he needed an aortic-valve replacement, the 80-year-old barber and his family had hoped he would be able to reopen the shop as his health was expected to improve. Doctors told Pat to take it easy and stay away from the shop while he waited to have surgery on March 23, but things were looking up.

Complications from surgery landed him 34 days in the hospital’s intensive care unit, but he only spent 13 days in rehab at Landmark of Lancaster after making significant progress and went home – notwithstanding the hospital’s recommendation that he should spend at least three days of rehab for every day spent in the ICU.

After making a remarkable comeback, Pat spent just eight days at home before he suddenly took a turn for the worse and died from a massive brain bleed Friday, May 19, while he was surrounded by loved ones at Central Baptist Hospital in Lexington.

“I lost my dear friend,” said Theresa Long, Pat’s daughter. “I lost somebody who was my rock. He was my go-to person, and I don’t have that anymore.”

Pat stood proudly behind five generations and crafted the classics, especially his famous flat top, for five bucks a cut as those beloved customers sat in his crimson Koken President chair.

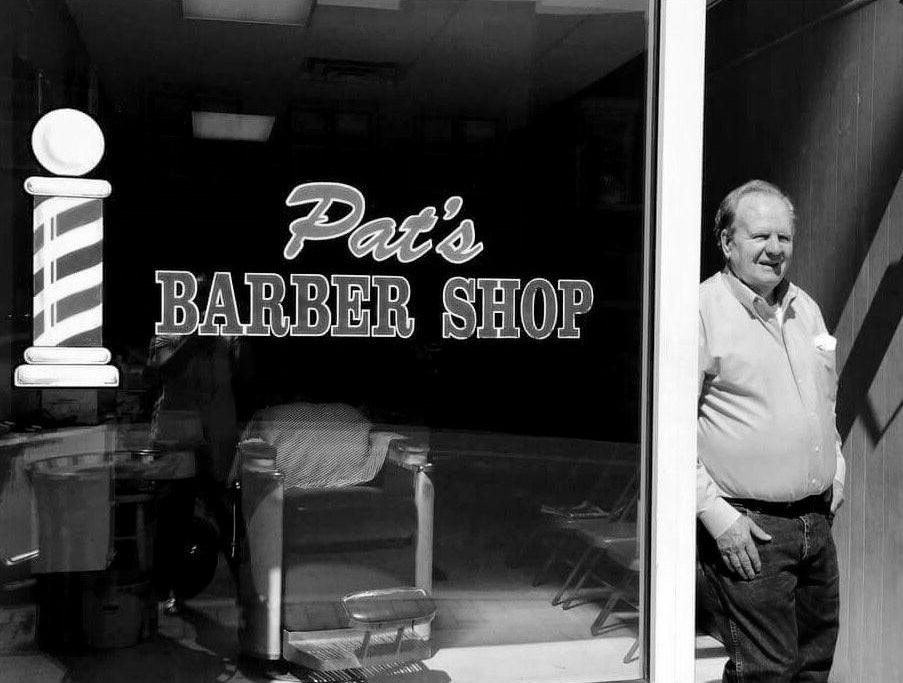

Pat Sanders stands at the entrance of his barbershop in this undated and provided photo.

Having added things up based on some rough numbers, his two children, Theresa and her brother, Patrick Sanders II, estimated their father had cut about 625,000 heads of hair during his decades of service to the community.

Stricken by grief, his adult children now wonder about all the conversations that took place while they weren’t in their father’s shop — all the political and religious revelations within its narrow walls that are now preserved by memories alone, and all the laughs and other iconic dad-moments that they may have missed at what would eventually become the oldest business in Stanford.

Both had visited every day, and they did so because they found joy in watching him work and relished his company.

“Now we don’t have that, so there’s a big ol’ huge hole,” Theresa said.

Pat was always at the shop and working before dawn, and he usually wouldn’t lock up until after dusk.

Only thing that begged his attention away from the shop was his civic duty, having served as a magistrate on the Lincoln County Fiscal Court and a Kentucky Colonel, as well as a member of the National Guard, the American Legion and the Blue Grass Community Action Board of Directors.

He also made house calls for sick people in the community and carried a suitcase for that purpose. Theresa said he continued to do that right up until he went in for his first surgery, even though his shop was closed.

“Didn’t matter who they were,” she said, noting his compassion for others. “Oftentimes, people would come in here and they didn’t have a dime to their name. He’d never charge them a penny to cut their hair.”

Every morning he’d wake up, get ready, hop in his Chevy pickup, drive into town and park at the city garage, and then he’d stop by Tommy’s Chevron Services to say a quick hello before taking a short walk down Main Street to the shop. When he arrived, he’d crack open his bible and pray before getting started.

If you had walked in at various points since 1959, the barbers under Pat’s employ might have been different, but everything else would have been more or less the same.

The window sign never changed. The Elgin Watches clock always ticked. If you had looked right under that clock, you would have been reminded of The Ten Commandments. Politicians’ business cards were strewn across the shelves. Same ol’ sinks, same ol’ mirrors, same ol’ drawers, same ol’ wood-panel walls.

“I know that my dad looked at that clock probably more than you could imagine,” Patrick said. “That was really the only thing I wanted out of here.”

That sense of familiarity was comforting to many of his patrons, especially to those who had watched Stanford change as they aged and the once-hopping town began to lose its luster.

“Of course there’s more going on, but there was a time that this town just stood still and there wasn’t anything around here,” Theresa said. “He watched it thrive and he watched it die, but he never left.”

Patrick said his dad may have witnessed both the high and low points in Stanford’s history but he never lost hope, especially since The Bluebird and other new businesses have attracted more people to town in recent years.

One-year-old Kyrus Kelsey got his first haircut from grandpa Pat Sanders in 2016 as the shop celebrated 57 years on Main Street. Photo by Abigail Whitehouse

Pat was the first person Bluebird owner Jess Correll met when he moved to Stanford, and his popular restaurant has been next door to the barbershop for the past five years.

“He was one of the finest men we’ve ever seen,” Correll said. “Stanford won’t be the same without Pat.”

If you went to the shop in its early years, chances are you would have caught Ezra Whitehouse snoozing in his own chair. “He didn’t work, but dad always kept him here because he was just part of the fixture,” Theresa said.

In one decade, you might have seen Daryl Barrett working the middle chair before it was stashed in the corner. In another, you might have seen Earl Lee Taylor working up front after a short retirement from his old barbershop across the street where Dale Reed’s is now.

If you popped in and snuck a peek in the back room during downtime, you probably would have found Charlie Brown of Fox Funeral Home and a few other locals passing the time by playing checkers while Pat cleaned.

Although he had a busy schedule, Pat managed to find some time during two or three years in the late 60s to run a dry-cleaning service called Linco Cleaners on Depot Street, and he also did some farming. He was a diehard Chevrolet fan and always kept a Camaro to drive around on Wednesdays and Sundays, his days off.

“Anything that went on, we had to make sure it happened on Wednesday or Sunday,” Theresa said. “We always kidded him … that if Patrick were to die, he’d make sure it was on Wednesday so dad wouldn’t have to take off work.”

Considering their shops have been right across the street from each other since Dale bought Earl Lee’s place about 25 years ago, you might have thought Dale was Pat’s greatest rival if you didn’t know they were such good friends, and even served as magistrates together.

Dale, 78, said they had known each other for practically their entire lives, and, despite their friendly competition, he and Pat cut each other’s hair since 1959.

“He was one of the best barbers I’d ever seen,” Dale said. “I’ll miss him. We had a lot of laughs together.”

Theresa took a coat rack, a table and the checkerboard as keepsakes, but most of the other stuff is going into storage until she and her brother can work up the courage to go through it. She said Pat’s old space will likely remain a barbershop upon renovations, and the chairs are going to be restored to maintain its nostalgic feeling.

“A little part of dad and the barbershop will live on,” she said.

Pat was born and buried in Waynesburg, but Patrick said his dad would want all his customers in Stanford to know how much he appreciated all the memories, love and dedication he had experienced with them here over the years.

“’He always said, ‘I’ve had a good life,’” Theresa said of her father, a longtime parishioner at Grace Fellowship Church. “He said, ‘If God calls me home, I’m ready to go.’”

Editor’s note: Information on Pat Sander’s medical stay at Central Baptist was provided solely by his family as the hospital declined to confirm any details.